Doctoral graduate Brenda Eap landed a job at a Washington, D.C., political action nonprofit.

Tag: Health Care

Keck Hospital of USC again earns ‘A’ hospital safety grade

The rating from independent watchdog organization The Leapfrog Group places the hospital among the safest in the country.

Keck Medicine of USC opens transplant care clinic in Las Vegas

The clinic is the first in Nevada to offer in-state heart transplant services.

Using art for medical healing

(Illustrations by Paul Blow)

Arts

Using art for medical healing

A vibrant collection of USC programs infuses arts activities into health care to soften the hospital setting, support patients’ recovery and lift their spirits.

In the USC-Verdugo Hills Hospital (USC-VHH) Breast Healthcare Center, an exhibit of oil paintings adorns the walls next to the 3D mammography machine. Each artwork depicts a stunning natural scene: Wildflower-studded cliffs framing an azure sea. A footbridge arching over a tranquil pond. Glass vases brimming with irises and sunflowers.

A cancer screening room may seem an unlikely venue for a gallery display. But the artist, Marijane Hebert, sought the opportunity to show her work here. A two-time breast cancer survivor and patient of the USC-VHH Breast Healthcare Center, Hebert knows firsthand how nerve-racking it can be to undergo breast cancer screening — and how art can be a refuge during diagnosis and treatment.

“When you hear the word ‘cancer,’ it’s very frightening,” says Hebert, 85, a La Cañada Flintridge resident who has exhibited in galleries in the United States and Europe. “I just thought that art would be fabulous to have in the Breast Healthcare Center to help create a calming atmosphere.”

Hebert’s exhibit was made possible by the USC-VHH Healing Arts Program, which mounts permanent and rotating exhibits by local artists in the hospital’s hallways and treatment spaces. Supported by the Sue and Steve Wilder Healing Arts Endowment, the program also allows hospitalized patients to select a work of their choice from a roving “Art Cart” to keep in their room during their stay and to take home.

“We focus on fine art reflecting positive images of nature and familiar scenery,” says Julie Shadpa, an art therapist by training who is co-chair of the Healing Arts Program and director of donor programs and strategic outreach for the USC-VHH Foundation. “Research has indicated that such imagery lowers stress and distracts from pain. … It gives people a sense of place and connection in the hospital environment, which can be stressful and unfamiliar.”

Art has been used as an adjunct to medical treatment since ancient times. But in the past few decades, a growing body of research has confirmed that viewing and creating art can benefit patients’ physical and mental well-being. The Healing Arts Program is among a robust collection of USC programs that combines the arts with medicine in creative and evidence-based ways to comfort patients and support their healing.

Fighting cancer with creativity

At the Institute for Arts in Medicine (I_AM) at the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, a wide range of expressive arts programming aims to improve clinical outcomes for patients.

In the Creative Corner, a cheerful arts studio in the hospital, patients can try their hand at fun projects like painting rocks with inspirational sayings or personalizing a hospital wristband. On Zoom, they can join poetry-writing workshops. From their hospital rooms, they can write, sing and record an original song with the help of a songwriter. In the Rare Book Room at the USC Norris Medical Library, they can plan a body painting session with artist-in-residence Savannah Mohacsi, who draws inspiration from archaic medical illustrations. She later turns the region of the body that is ailing the patient into a creative canvas.

“Creative interventions such as music, poetry and painting can significantly decrease anxiety, depression and a lot of the negative psychological aspects associated with cancer and its treatment,” says Jacek Pinski, associate professor of medicine in the divcarolynmeltzer.comision of medical oncology at USC Norris and executive clinical director of I_AM. “The immune system, which plays a critical role in fighting cancer, gets boosted by these interventions,” he adds.

We call ourselves ‘I_AM’ for a reason: We believe that creative expression brings people closer to their true identities.

— Genevieve “Viva” Nelson

Patients can also don virtual reality (VR) goggles to engage with artistic renderings of natural settings like waterfalls and beaches. Pinski and the I_AM team are currently conducting a clinical trial evaluating the impact of these VR experiences on pain and anxiety during painful bone marrow biopsies.

Yet data doesn’t easily capture some of the most impactful aspects of I_AM’s arts programming. The activities allow patients to reflect on their experiences with illness, integrate them into their larger life journeys and glean wisdom that fortifies them through ongoing challenges.

“We call ourselves ‘I_AM’ for a reason: We believe that creative expression brings people closer to their true identities,” says Genevieve “Viva” Nelson ’18 (SCA), the creative director and co-founder of I_AM. “Engaging with the arts and engaging with our team allows patients to recognize their importance and their value and connect to their extraordinary capacity to be creative.”

Clowning around

Twice a week, children at Los Angeles General Medical Center receive a visit from specially trained USC staff. These visitors aren’t wearing white lab coats or surgical scrubs — they’re sporting red noses and ridiculous costumes. They play ukuleles, blow bubbles, juggle scarves and devise silly scenarios.

They’re medical clowns from USC Comic+Care, a program at the USC School of Dramatic Arts that employs comedic arts to support children grappling with illness.

Both disease symptoms and the hospital environment itself can dim children’s natural propensity for creative play. “You are given a [hospital] gown and put into a room that is completely unfamiliar to you and rather sterile,” says Zachary Steel, assistant professor of theater practice at the USC School of Dramatic Arts and director of USC Comic+Care. “We are trying to reframe the hospital visit into something with the potential for joy and play.”

The laughter that the clowns spark is medicine of its own. Research has shown that laughter can do everything from boosting immune and endocrine responses to decreasing blood pressure and feelings of despair. USC Comic+Care is currently partnering with the hospital’s pediatric oncology and hematology clinic to conduct a study on the effect of clowning on children’s pain perception and levels of stress and anxiety during blood draws.

Steel is also training the next generation of medical clowns. He teaches introductory and advanced medical clowning, the latter offering USC undergraduates the opportunity to do some clowning of their own with the children at Los Angeles General Medical Center.

“It’s beautiful when you hear the children’s laughter,” Steel says. “It’s a recognition of, ‘I still have the capacity for joy. I can still play. I’m still a kid.’”

Waltzing toward better health

Older adults, too, can benefit from the lightheartedness that arts activities inspire. Dance is one example: The art of movement offers neurological, social and emotional benefits to those struggling with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s disease.

“Dance can trick our brains into working better,” says Patrick Corbin, associate professor of practice at the USC Kaufman School of Dance. Research has shown that Parkinson’s patients who participate in dance have improved speech, fewer tremors, better balance, decreased rigidity and slower disease progression compared to those who do not.

Creative interventions such as music, poetry and painting can significantly decrease anxiety, depression and a lot of the negative psychological aspects associated with cancer and its treatment.

— Jacek Pinski

Corbin teaches “Dance and Health: Dance and Parkinson’s,” an undergraduate course that combines movement instruction with guest lectures from experts in a variety of health science disciplines, including the Department of Neurology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, the USC Mrs. T.H. Chan Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy at the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC, and the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology.

Students put that knowledge into action through fieldwork in the community. They observe and participate in dance classes for Parkinson’s patients taught at Lineage Performing Arts Center in Pasadena, Calif., a partner of the Keck School of Medicine. For their final exam, students teach a segment of the Lineage class on their own.

The “Dance and Health: Dance and Parkinson’s” class is part of a series of adaptive dance classes that Corbin conceived and developed with the support of Arts in Action, part of USC Visions and Voices. In fall 2023, his class focused on Down syndrome and brought dancers from Free 2 Be Me Dance — an organization that serves people with Down Syndrome — to USC Kaufman for instruction. Another course for children with autism spectrum disorders is in the works. Corbin praises his collaborators in USC’s health sciences schools who are helping him illuminate the power of dance to influence the well-being of marginalized communities.

“These wonderful doctors are really seeing the scientific value of the connection between the arts and sciences,” Corbin says. “I think we’re just at the beginning of creating a world where better lives are accessible to people who may have been overlooked before.”

Healthier together

Building new partnerships between USC’s health sciences and arts schools is a priority for Josh Kun, vice provost for the arts. In March, he and Michele Kipke, associate vice president for strategic health alliances at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, led a daylong retreat for deans and faculty to spark new research collaborations between the arts and health sciences. Their efforts reflect USC President Carol Folt’s “moonshot” on transforming health sciences, which seeks to expand health sciences work across the university.

Kun notes that among their many benefits, USC’s varied arts in medicine programs provide patients an antidote to the isolation of illness.

“When we hear a song, when we watch a dance performance, when we watch a film, when we look at a painting or a sculpture, one of the things that can happen is you realize you are not alone,” Kun says. “Somebody else’s experience touches your own life.”

Hebert — who, in addition to her permanent exhibit in the USC-VHH Breast Healthcare Center, has an exhibit on display in the main USC-VHH building through June — echoes his sentiments.

“When we go through illness, we have to give back and share with others, so they can know that you do get through these things,” she says. “Life does move forward.”

Meet some of the doctors healing USC’s athletes

Dr. Alex Weber (center) assists player Travis Dye during a football game in 2022. (Photo/Katie Chin)

Athletics

Meet some of the doctors healing USC’s athletes

How the orthopedic specialists at Keck Medicine of USC and USC Student Health keep Trojan athletes — and the L.A. Kings — moving.

Charles Mills hoped for a different start to his career on the USC water polo team. In an exhibition match last September against Golden West College, an opposing player’s arm smashed down onto Mills’ wrist as he defended a shot. Initially, Mills says the pain wasn’t too severe. But on his way home that night, the first-year goalie fell off his bike onto that same wrist. The pain kept him up for much of the night.

“That next morning, I knew something was up,” Mills says.

He immediately visited the USC athletic trainers, who directed him to an orthopedic specialist at Keck Medicine of USC. Seth Gamradt gave him the news: Mills had broken the scaphoid bone in his left wrist.

Less than a month into his freshman campaign, just like that, his season was over.

“I was in complete denial,” Mills says. “I thought I had just jammed my wrist really hard — I didn’t think I’d broken it, let alone that I’d be out two months.”

Although Mills says it was a tough pill to swallow, Gamradt and his team immediately shifted the discussion to recovery.

“Dr. Gamradt and his team comforted me and told me I was going to get through this, which helped me not freak out too much,” Mills says. “I was still completely crushed, but I had complete trust in them.”

A surgery, two months in a cast and some physical therapy later, Mills made a full recovery. He credits it to the care he received from the athletic trainers and health care team in the athletic medicine program at USC Student Health, along with his surgeon Luke Nicholson and the orthopedic team at Keck Medicine of USC. In a sport rife with shoulder and hip injuries and the occasional broken wrist, access to top-notch care is crucial.

The care here, at USC, is completely unmatched. Everything was super organized, and there was full transparency.

— Charles Mill

Fortunately for Mills, his teammates and the roughly 700 other Trojan student-athletes, the athletic specialists from Keck Medicine of USC provide some of the best care in the region.

“The care here, at USC, is completely unmatched,” Mills says. “Everything was super organized, and there was full transparency — I trusted the process, and it worked out 100% well for me.”

His teammate Max Miller — a first-team all-American 2-meter — agrees. He credits the doctors as part of the reason Trojans can continue playing after an injury. “It’s a very comforting feeling to be able to just do my thing in my sport, and then if something ends up happening, I know they’ll find a way to fix it,” he says.

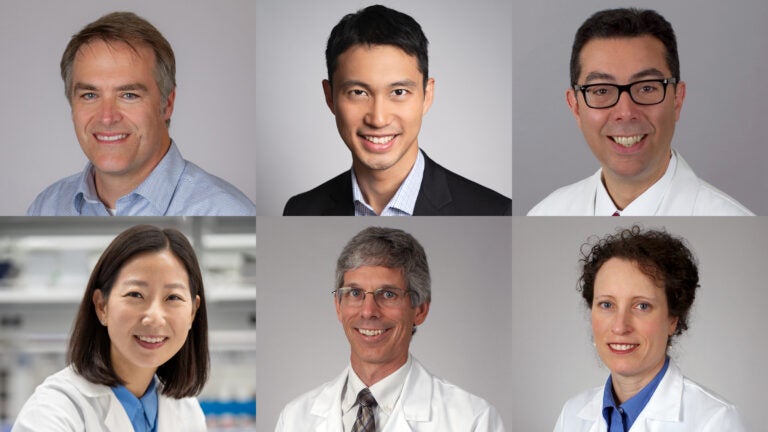

A dream team of sports doctors

When it comes to athletics injuries, few have seen more than Gamradt and Alex Weber. As orthopedic surgeons and team doctors, they’ve been on the sidelines for championship games and witnessed some of the greatest athletes compete at the highest level.

Gamradt — lead physician for Trojan football for the past 11 years — also worked at the professional level with the NFL’s New York Giants before coming to the West Coast. He is an orthopedic surgeon with Keck Medicine of USC and director of Athletic Medicine, a department in USC Student Health that oversees health care for student-athletes.

“It was an opportunity that I couldn’t turn down,” Gamradt says. “It’s an incredible institution, and the Trojan Family is real — anytime I’m wearing USC gear when I’m out and about, I’ll always get a ‘Fight On!’”

For the past eight years, Weber has served as a team physician for USC Athletics as part of USC Student Health and Keck Medicine of USC, while also serving as chief of the USC Epstein Family Center for Sports Medicine at Keck Medicine of USC. In addition, he is the medical director and head team physician of the NHL’s Los Angeles Kings.

Joseph Liu and Cara Hall have been at Keck Medicine of USC for three years. Both work with the L.A. Kings, and all four physicians provide orthopedic care to all 21 Trojan athletic programs.

“Sometimes it’s an 81-year-old, and sometimes it’s an 8-year-old, sometimes it’s a high school athlete hoping to be a collegiate athlete,” Weber says. “Then sometimes it’s a collegiate athlete trying to be a professional athlete, and sometimes it’s a professional athlete trying to get back to his livelihood. Ultimately, all of those scenarios fall into the same bucket of someone high-functioning losing that function, and getting them back to doing what they love.”

Team mentality

The sports medicine team helps make those moments possible, whether that’s Gamradt working the sidelines of Trojan football games, Weber sitting courtside at men’s basketball games, Hall tending to the Women of Troy in a packed Galen Center or Liu treating the members of the men’s volleyball team.

“Working with the women’s basketball team has really been the best part of the job for me,” Hall says. “It’s such a small team, and we have come leaps and bounds from where we were a few years ago. Seeing them excel at what they do and traveling on the road with them and seeing them make it to March Madness last year — it’s rewarding for everyone involved.”

The team of orthopedic surgery specialists at Keck Medicine of USC are some of the most highly regarded physicians in L.A., so much so that the Kings, a $2 billion NHL team, wanted to partner with them to take care of their athletes.

“One great thing about taking care of the hockey guys is that there’s a culture in hockey that the guys want to play,” Weber says. “We do that within safe parameters — we don’t let people go back when it’s unsafe to be on the ice — but I think the culture in hockey is get fixed up so you can get back out there and play hard for your teammates.”

Sports medicine in the age of social media

As the team of physicians looks toward the future of their profession, they note that social media has had a significant impact on sports medicine, both good and bad.

“There are a lot of what we call ‘Twitter doctors’ who are out there speculating on the injury and how long this athlete’s going to be out. Social media has become the biggest influence on the scrutiny of athletic injuries,” Gamradt says.

For Hall, the increased attention has spotlighted her chosen profession, which she hopes will inspire the next generation of sports physicians.

“The number of students that have reached out to me just from finding my name on the [Keck Medicine] website — medical students or even undergrad students who are interested — has exceeded what I was expecting,” Hall says. “Anyone interested in physiology or kinetics and movement from a science or physical therapy perspective, I think there’s probably a growing interest compared to what it used to be, which is great to see.”

Caring for all

While these doctors have treated their fair share of all-stars and all-Americans, they’ve also treated plenty of weekend warriors. Aside from dealing with agents and the financial implications of a top-level athlete’s injury and recovery, they all say that the mission for treating their patients is the same.

“It’s so hard to pick my favorite part of the job because it’s so multifaceted,” Gamradt says. “I get to teach residents, medical students and fellows how to do surgery. I get to care for patients of all ages and make them better with or without surgical treatment, and then I have the added bonus of being the team physician.”

That type of attitude influences the athletes in return. Whether on the field or off, it’s nice to know everyone’s on the same team.

“I still see Dr. Gamradt and the other trainers around campus, and even my full recovery, they’re always asking me how I’m doing and if I need anything — so, it’s not just a one-and-done deal,” Mills says. “I know that they always have my back.”

Art in medicine helps doctors, too

“The Bump” is a photograph taken by Carolyn Meltzer, dean of the Keck School of Medicine of USC. (Photo/Courtesy Carolyn Meltzer)

Health

Art in medicine helps doctors, too

At USC, weaving art into medical practice benefits doctors and patients.

Carolyn Meltzer, dean of the Keck School of Medicine of USC, is a leading scholar in neuroradiology. But on her website, carolynmeltzer.com, you won’t find any information about her extensive research in brain imaging. Instead, you’ll find her portfolio of fine art photography.

Meltzer, whose art has been featured in more than 50 solo and group exhibits in the United States and Europe, believes that the visuospatial skills she has cultivated through photography strongly inform her work in radiological imaging. “Having this artistic outlet makes me a more effective colleague and leader on the medicine and scientific side,” she says.

Meltzer’s experience is one example of how the arts can be a vital resource for medical practitioners. Artistic endeavors can sharpen diagnostic skills, help physicians tend to their own wellness and deepen understanding of the human condition.

“I don’t think you can be a fully compassionate doctor without having some of the skills that can only be learned in humanistic and artistic pursuits,” says Pamela Schaff, professor of clinical medical education, and family medicine, and pediatrics (educational scholar).

Schaff is the director of Keck School of Medicine’s Humanities, Ethics, Art, and Law (HEAL) Program, which has been weaving the arts into the core curriculum for medical students since its founding in 1985. The multipronged program includes art exhibits by — and discussions with — artist-patients whose artwork explores the experience of living with diseases that students learn about in their classes. “When you’re just reading a textbook, or just even interviewing a patient, you don’t understand diseases in as fully realized a way as when you’re also seeing the artwork that has been born out of the experience,” Schaff says.

Fourth-year medical student Tejal Gala has enjoyed immersing herself in the artist-patients’ exhibits in the medical school’s Hoyt Gallery and participating in the discussions. “It’ s a wonderful reminder that patients are more than a constellation of symptoms,” she says. “When we really pay attention to their emotions and how they’re feeling, we’re tapping into the art of medicine just as much as the science.”

The HEAL Program also offers medical students the opportunity to participate in the arts through creative writing workshops and music lessons. Gala herself is a photography enthusiast who recently published Keck in Bloom, a coffee table book of photos of the varied plant life on USC’s Health Sciences Campus. She found that exploring nature with her camera was a powerful stress reliever.

“Having time to engage the arts is an important part of … taking care of ourselves, so we can be there for our patients,” Meltzer says.

The dean hopes to bring USC’s many well-established arts in medicine programs under a more cohesive umbrella. She also envisions launching new interdisciplinary ventures between the Keck School of Medicine and USC’s arts schools. In February, the Department of Radiology debuted the Center for Advanced Visual Technologies in Medicine, which adapts novel applications of digital and 3D visualization techniques to patient care, education and research. The center connects creative technologies across multiple units and schools, including the USC School of Cinematic Arts.

Arts collaboration “is a strategic priority for the Keck School of Medicine because it creates unity and supports our practitioners and our patients,” Meltzer says.

11 USC researchers named National Academy of Inventors senior members

The National Academy of Inventors is a nonprofit member organization that encourages inventors in higher education. (Photo/iStock)

Science/Technology

11 USC researchers named National Academy of Inventors senior members

The honor recognizes innovation that has a real impact on the welfare of society.

Eleven USC researchers on Tuesday were named senior members of the National Academy of Inventors, a nonprofit member organization that encourages inventors in higher education.

Election as an NAI senior member recognizes remarkable innovation producing technologies that have brought, or aspire to bring, real impact on the welfare of society. The honor also represents growing success in patents, licensing and commercialization, while educating and mentoring the next generation of inventors.

The USC members of the NAI Class of 2024 are Peter A. Beerel, Yang Chai, Denis Evseenko, Qiang Huang, Justin Ichida, Bart Kosko, Peter Kuhn, Daniel A. Lidar, J. Andrew MacKay, Wei-Min Shen and Travis Williams.

“Today’s announcement reflects the amazing innovation that takes place at USC every day,” USC President Carol Folt said. “These 11 outstanding faculty members — the most NAI inductees from USC in any one year — showcase our unique multidisciplinary, multischool approach. Their work crosses fields of dentistry, engineering, medicine, pharmacy and more to create a future of possibility and opportunity. We salute these inductees for their well-earned recognition.”

The 11 Trojans join 20 current and emeritus USC faculty members in the NAI ranks. They will officially be recognized on June 17 during NAI’s annual meeting.

“This year’s cohort of 11 USC inductees as senior members of the National Academy of Inventors is a huge honor,” said Ishwar K. Puri, USC senior vice president of research and innovation. “The breadth of expertise recognized in this year’s cohort testifies to the wide array of world-leading inventors, engineers, scientists and clinicians at USC. Their innovations have invented tomorrow’s solutions, which improve human lives and fuel economic growth.”

Peter A. Beerel

Professor of electrical and computer engineering, USC Viterbi School of Engineering

Beerel has a history of innovation in the area of Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI), the process of designing semiconductor chips with millions of transistors. His more recent significant contributions are in the areas of hardware security, superconducting electronics and machine learning.

Beerel joined the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering in 1994, and he’s currently a full professor and associate chair of the computer engineering division. He’s also a research director and distinguished principal scientist at USC Viterbi’s Information Sciences Institute. Previously, he was the faculty director of innovation studies at the USC Stevens Center for Innovation from 2006 to 2008 and co-founded TimeLess Design Automation in 2008.

Yang Chai

University Professor, George and Mary Lou Boone Chair in Craniofacial Molecular Biology and associate dean of research at the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC; University Professor of Biomedical Sciences, Otolaryngology — Head & Neck Surgery, and Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC

Chai has invented a system meant to regenerate skull bone to address deformities, comprising a 3D-printed scaffold seeded with stem cells. The technology comes out of discoveries from his laboratory about the molecular and cellular mechanisms behind congenital birth defects.

Chai recently launched early interactions with the Food and Drug Administration, on the path to phase 1 trials of the scaffolds in patients. In addition, he continues work toward an innovative tissue regeneration system for patients with cleft palate, a condition that is the major focus of his work. His research is motivated by his own experience as a clinician interacting with parents of children born with deformities to the face and head.

“The surgery was always successful, but I didn’t have any answers about why the birth defect happened, whether a future child in the family may also have one or how it could be prevented,” he said. “We tried to understand the basic mechanisms, then shifted our efforts to use some of the knowledge we gained. We aim to provide a biological solution for a biological problem, instead of using a titanium plate to repair the skull defects.”

An extended version of this profile of Chai appears on Keck School of Medicine website.

Denis Evseenko

J. Harold and Edna La Briola Chair in Genetic Orthopaedic Research, vice chair for research, director of skeletal regeneration and professor of orthopedic surgery, stem cell biology and regenerative medicine, Keck School of Medicine of USC

Evseenko has created a series of treatment technologies that address injury and illness of the joints.

One is an injection designed to calm inflammation in osteoarthritis and potentially supplant joint replacement surgery. (Phase 1 clinical trials are imminent.) Another is a surgical implant that delivers stem cell-derived cartilage to replace damaged tissue from sports injuries and prevent degenerative joint disease, with first-in-human trials likely to begin this year. Most recently, Evseenko and his team have invented a drug to moderate a mechanism of the immune system that misfires and attacks aging cells, with potential application for inflammation affecting multiple body systems.

For Evseenko, election to the NAI validates the time and effort he has devoted to driving his discoveries from the lab to application.

“It’s meaningful to know that all the small steps we took, day after day, to move us forward toward our goals were leading in a fruitful direction,” he said. “I had to make some difficult decisions along the way, and this recognition tells me that they were the right ones.”

An extended version of this profile of Evseenko appears on the Keck School of Medicine website.

Qiang Huang

Professor of industrial and systems engineering, and chemical engineering and materials science, USC Viterbi

Huang is an expert in the field of smart manufacturing.

Huang’s research focuses on how machine learning can be harnessed for additive manufacturing (3D printing). His work also covers quality control theory and methods for personalized manufacturing, domain-informed machine learning methods for smart manufacturing, and nanomanufacturing analytics. Huang holds five U.S. patents on 3D printing accuracy control. The Huang Lab has been developing fabrication-aware machine learning algorithms and computation-driven quality control tools to make 3D printing smarter.

Justin Ichida

John Douglas French Alzheimer’s Endowed Professor in Regenerative Medicine, associate professor of stem cell biology and regenerative medicine, Keck School of Medicine

Ichida centers his research on amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), a rare, deadly neurodegenerative disorder that occurs during middle age and disrupts the ability to control muscle movement. He has developed a technology that can turn cells from ALS patients’ blood samples into nerve cells.

The invention is one of the first successful attempts to drive the development of adult cells backward to the stem cell stage and then coax them to grow into a different type of cell. From the Petri dish, he and his team can then delve into the mechanisms behind the illness — which are yet poorly understood — and test potential treatments.

“ALS has a huge unmet need,” Ichida said. “It’s hard to study by traditional methods because we don’t know what the genetic causes are for most patients. Our technology allows us to unlock insights that we couldn’t otherwise.”

An extended version of this profile of Ichida appears on the Keck School of Medicine website.

Bart Kosko

Professor of electrical and computer engineering, USC Viterbi; professor, USC Gould School of Law

Kosko has enjoyed an eclectic career at the university. He came to USC from Kansas on a scholarship for music composition, then earned bachelor’s degrees in philosophy and mathematical economics, inspiring his neural work. The university hired him in 1987 to join the then-new Neural, Informational and Behavioral Sciences program. He has also published several textbooks, trade books (including, in 1993, Fuzzy Thinking: The New Science of Fuzzy Logic) and novels.

Last year, Kosko received the prestigious Donald O. Hebb Award from the International Neural Network Society for his careerlong contributions to the field of neural learning.

Peter Kuhn

Dean’s Professor of Biological Sciences, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences; professor of medicine and urology, Keck School of Medicine; professor of biomedical engineering and of aerospace and mechanical engineering, USC Viterbi; director, Convergent Science Institute in Cancer, USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience

After early success in drug development for cancer, Kuhn turned his sights to leading the charge in advancing liquid biopsies, a type of blood test that detects and characterizes circulating tumor cells. Although he focuses on breast cancer, a disease his mother faced, his inventions have been applied for treating prostate cancer as well. His technology has been in use for oncology care since 2016.

A personal highlight was when others started using his invention and the thrill derived from seeing that success: A colleague published a clinical study showing that one of his inventions was effective in differentiating between which patients would benefit from one treatment over another in fighting cancer.

“That was the best day of my life, and I didn’t even know about the study before it came out,” Kuhn said with a smile. “It wasn’t just seeing this striking result. It was knowing that they could do it without me. There are a lot of hurdles, and it’s an incredible feeling when something makes it through — and makes a difference for patients.”

Extended versions of this profile of Kuhn appear on the USC Dornsife website and the Keck School of Medicine website.

Daniel A. Lidar

Professor of electrical and computer engineering, chemistry, and physics and astronomy, USC Viterbi

Daniel A. Lidar was recognized for his inventions in the area of quantum computing, which have led to six issued patents. These patents cover areas such as quantum teleportation, error correction, and optimization.

Lidar joined USC in 2005, and he is the holder of the Viterbi Professorship of Engineering. He has joint appointments in electrical and computer engineering as well as chemistry and physics. He’s also the director of the USC Center for Quantum Information Science and Technology and the co-director of the USC-Lockheed Martin Center for Quantum Computing.

Andrew MacKay

Gavin S. Herbert Associate Professor of Pharmaceutical Sciences, USC Alfred E. Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences

MacKay’s lab is focused on engineering protein-polymer tools that hold the potential to transform the development of precision, multifunctional drug carriers.

“Drug delivery in the eye and cancer is often limited by access to and retention at the target site,” explained MacKay, who has six issued U.S. patents, with four focusing on ocular applications of his technology. “Our strategy is to repackage drugs and functional peptides into protein-polymers that control release and reduce toxicity.”

“Our group has recently made significant breakthroughs by assembling polypeptide ‘microdomains’ on the surface of and inside living cells,” added MacKay, who holds secondary appointments in biomedical engineering and ophthalmology and serves as executive editor for the journal Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. He also serves as a panel reviewer for the U.S. National Institutes of Health, primarily as a member of a nanomedicine-focused study section. “When decorated with functional proteins, these polypeptides are helping us to precisely modulate cellular biology and design new therapies.”

Wei-Min Shen

Associate professor of computer science practice and a research associate professor in computer science, director of the Polymorphic Robotics Laboratory, USC Viterbi; associate director of the Center for Robotics and Embedded Systems at USC

Shen’s research interests include self-reconfigurable and metamorphic systems, autonomous robots, machine learning and artificial intelligence. He is the author of Autonomous Learning from Environment, a book that explores how machines learn from their environment based on “surprises.”

He has served as chair and committee member for international conferences and workshops in robotics, machine learning and data mining, and as editorial board members for scientific books and research journals. His research activities have been reported by leading scientific journals such as Science and Nature, and in media outlets including CNN, PBS and Discovery.

Travis Williams

Professor of chemistry, USC Dornsife

Williams, who holds 10 patents and numerous awards recognizing the inventive value of his work, said being named an NAI senior member is a result of USC’s visionary support of innovators like himself.

“NAI recognition falls out of the university’s deliberate decisions to invest in patenting bizarre things from my lab, tenuring someone who quit working on what he was hired to do, and stoking innovation through the Wrigley Prize and the [National Science Foundation’s] I-Corps hub,” he said. “While I’ve been an enthusiastic product of my environment, USC Dornsife and the university engineered this through a generations-old commitment to innovation and public impact.”

Williams’ research has borne considerable fruit, including Closed Composites, which aims to recycle carbon fiber materials from old aircraft parts, and Catapower Inc., converting used oil from deep fryers into biodiesel and environmentally sound antimicrobial agents. Williams has even co-developed a method to turn plastic waste from the Great Pacific Garbage Patch into compounds to make pharmaceuticals and other useful products.

An extended version of this profile of Williams appears on the USC Dornsife website.

About the National Academy of Inventors

The NAI was founded to recognize and encourage inventors with U.S. patents, enhance the visibility of academic technology and innovation, encourage the disclosure of intellectual property, educate and mentor innovative students, and create wider public understanding of how its members’ inventions benefit society. The academy now comprises 4,600 individual members at more than 300 universities, governmental agencies and nonprofit research institutes worldwide.

USC’s Caitlin Dawson, Landon Hall, Greta Harrison, John Hobbs, Darrin Joy, Laura LeBlanc, Michele Keller, Paul McQuiston and David Medzerian contributed to this report.

First NEMO Prizes fund research partnerships at the intersection of health and engineering

One group of NEMO Prize recipients consists of Brian E. Applegate, Wade Hsu and John S. Oghalai (top row, from left); the other group is Eun Ji Chung, Ken Hallows and Nuria Pastor-Soler. (Hsu Photo/Courtesy of Wade Hsu; Chung Photo/Chris Shinn; all other photos/Ricardo Carrasco III)

Science/Technology

First NEMO Prizes fund research partnerships at the intersection of health and engineering

Awards were given to two USC research teams to fund collaborations between engineering and one or more of the university’s five health sciences schools.

USC’s Office of the Senior Vice President for Health Affairs has awarded the university’s inaugural NEMO Prizes to two teams of USC researchers across the University Park and Health Sciences campuses.

The NEMO Prize originates from a generous gift from Shelly and Ofer Nemirovsky. After Ofer Nemirovsky, a University of Pennsylvania business and engineering graduate, started the prize at his alma mater, the couple looked for an opportunity to do the same at USC, from which Shelly Nemirovsky graduated in 1985 and now serves on the Board of Trustees and as a member of the President’s Leadership Council.

“It’s really life-affirming for me to watch what can happen when the right minds get in the right room together,” Shelly Nemirovsky said. “The notion of putting the school of engineering and school of medicine together, and what they might accomplish — it’s just extraordinary.”

The winners of the highly selective $125,000 prizes — which will be presented annually to two teams for the next five years — proposed projects designed to bridge the gap between ideas and clinical breakthroughs in health and engineering collaborations. The prize aligns with President Carol Folt’s Transforming Health Sciences “moonshot,” which leverages USC’s research, medical training and clinical care to innovate and better serve patients and the community.

One of the winning projects, “RNA-BASED Nanoparticle Therapy for Polycystic Kidney Disease,” includes Keck School of Medicine of USC Professor Ken Hallows and Associate Professor Nuria Pastor-Soler, director and co-director, respectively, of the USC Polycystic Kidney Disease Clinic at Keck Medicine of USC, in collaboration with Associate Professor Eun Ji Chung, the Dr. Karl Jacob Jr. and Karl Jacob III Early-Career Chair at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering. The trio aims to perfect a therapy to target the root cause of polycystic kidney disease, before patients need dialysis or a kidney transplant.

The second group of prize winners includes electrical and computer engineering professor Wade Hsu and otolaryngology — head and neck surgery and biomedical engineering professors Brian E. Applegate and John S. Oghalai in a project titled “Through-Bone Optical Tomography of the Human Cochlea.” Prize funds will go toward developing a method for imaging the inner ear to address issues related to hearing loss and vertigo.

“These awards are an exciting reflection of the power of collaboration between engineering and health sciences, and how individual strengths are magnified when researchers from different schools combine their skills, expertise and dedication to scientific discovery,” said Steven D. Shapiro, USC’s senior vice president for health affairs. “Together, we are stronger as we continue our mission of delivering lifesaving medical care and research.”

Targeting the root cause of disease

Hallows describes polycystic kidney disease (PKD) as one of the most common, potentially lethal genetic diseases, cutting across all backgrounds. According to the research team, roughly half of patients with PKD will need kidney replacement therapy by the age of 50 to 60 years old.

The only FDA-approved therapy for PKD is a drug called tolvaptan, which isn’t well-tolerated in a large percentage of patients, Hallows said. Because the medication is taken orally, it can affect other organs in the body and cause issues such as frequent urination and liver dysfunction.

“There’s really a need for new therapies [for PKD] that are well-tolerated and target the root cause of the disease while correcting downstream signaling pathways that are dysregulated in the disease,” Hallows said. The team specified that almost all people with PKD have a mutation in one of two proteins called polycystins, which are encoded by the genes PKD1 and PKD2. These proteins are important for normal cellular function and growth control, as well as the polarity of cells that line the kidney, liver and other organs.

“The therapy that we won the NEMO Prize for is actually targeting those underlying mutations,” Hallows said. The team plans to address the genetic basis of the disease directly through mRNA delivered using nanoparticles, a method Hallows and Chung have collaborated on for the past seven years. While nanoparticles have been used as delivery systems in medicine for years — including with drugs to treat other diseases in other tissues — the team’s method is unique in that the delivered mRNA will go straight to the kidney to target the specific mutation found in the majority of PKD patients, ideally without side effects in other parts of the body, Chung said.

Chung, a nanoparticles engineer, first began developing nanoparticles designed to treat heart disease as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago. She noticed that the nanoparticles would go to the kidneys when the size and surface was tuned, which sparked an “aha” moment for the engineer.

“It was a coincidence that ultimately led to a lot of new innovation in my group,” said Chung, whose team became well-known for kidney nanomedicine after the discovery. “For the kidney, there’s just been a lack of innovation.”

When Chung made the move to USC, she reached out to Hallows, who shared his research interest in PKD that he was already working on with Pastor-Soler. The pair have been collaborating since then.

“The NEMO Prize has the potential to be transformational,” Pastor-Soler said. “The fact that they’re putting resources to support these types of collaborations is really encouraging and really timely.”

Using innovation to treat a growing health issue

The second winning USC team also views their NEMO Prize as an opportunity to use innovation to address common, hard-to-treat illnesses. According to the World Health Organization, by 2050 nearly 2.5 billion people will be living with some degree of hearing loss worldwide. At least 700 million will need some form of rehabilitation services. While there are many health issues that can lead to a diagnosis of hearing loss and vertigo — another issue involving the inner ear — Oghalai said there are few options for pinpointing a root cause. “MRIs and CT scans are all we have right now, and the resolution is too low to see any of the cells or tissues,” he said.

Applegate and Oghalai have worked toward addressing this issue for many years using a technique called optical coherence tomography (OCT) — commonly used by ophthalmologists to look at the inner part of the eye — to image the inner ears of both human and mouse subjects. While the technique has been very successful in mice, imaging human subjects has been challenging because our inner ear is blocked by a “thicker layer of bone,” Hsu said. This is an issue because bone scatters light, distorting imaging attempts of the inner ear. “The reason we send a telescope into space is so you don’t have the distortion of trying to look at a star through the atmosphere,” Oghalai said. He explained that the equivalent in a human would be sticking a tiny endoscope into the inner ear, which would be damaging.

Recently, however, Hsu’s group has begun developing a computational imaging method called scattering matrix tomography (SMT) that uses computer applications typically used in astronomy to improve the resolution and depth of imaging for the inner ear.

With their NEMO Prize, the three hope to join forces to use Hsu’s computational imaging method to overcome the limitations Applegate and Oghalai have experienced with the OCT technique.

“Nobody has been able to image the inner ear of humans with the resolution needed up to now,” Hsu said. “We hope to be the first to do that.”

The team is currently using preliminary technology from this approach to scan the outer ear of patients while continuing to do clinical trials on dead mice. This immediate goal is to move on to live mice and, once Hsu’s algorithms are perfected, live humans. Their long-term goal is to develop a hand-held, noninvasive SMT-OCT device for accurate imaging from the ear canal, Applegate said. The medical instrument would aid in diagnosis, creation of therapeutic interventions and the investigation of new therapies to treat and prevent hearing loss and vertigo.

“We just are so thankful for SVP Shapiro’s office for organizing this, and for the Nemirovsky family for donating the funds to support this prize,” Oghalai said. “We’re super excited to get this to work, and I think it’s going to help people.”

Partnership as a key to success

“We are thrilled that our faculty will receive NEMO Prize funding to pursue their research on the human cochlea and on polycystic kidney disease,” said Yannis C. Yortsos, dean of USC Viterbi. “Their partnership with their research collaborators from the Keck School of Medicine is key to the success of their projects. Such interdisciplinary collaborations not only form an essential element of the NEMO Prize but are necessary in today’s increasing convergence of the disciplines in health sciences and engineering.”

The NEMO Prize Steering Committee sought applicants who proposed exciting health-engineering collaborations that will be competitive for future follow-up funding from other sources and have the potential to improve health, health outcomes and health delivery down the road.

“Sometimes it gets a little siloed in academia; this [award] gives people the opportunity to share in a way where they’re not competing, but rather working together,” said Shelly Nemirovsky, whose brother and two out of three children also attended USC. The couple also gave a gift to create the Nemirovsky Residential College at USC Village in 2017 and funds the Shelly and Ofer Nemirovsky Provost’s Chair. “My hope is that researchers continue to talk across schools to find the great palliative ways to treat some of these horrible diseases out there. I think the possibilities are really limitless.”

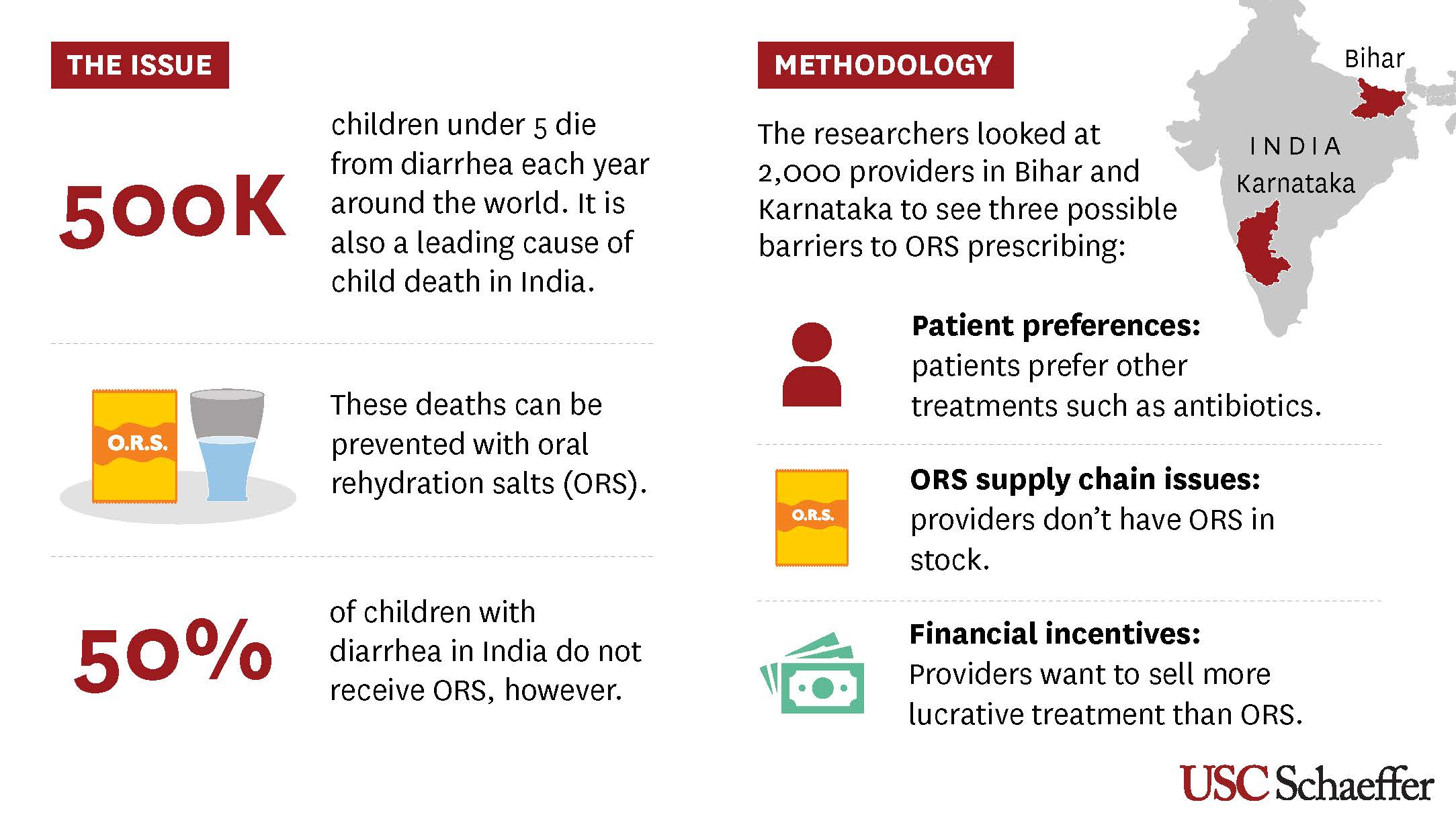

This common medication could save half a million children’s lives each year. So why is it underprescribed?

A new study by researchers at USC explains why kids aren’t getting a cheap, effective treatment for diarrhea.

Contact: Nina Raffio, raffio@usc.edu or 213-442-8464; Jenesse Miller,jenessem@usc.edu or 213-810-8554

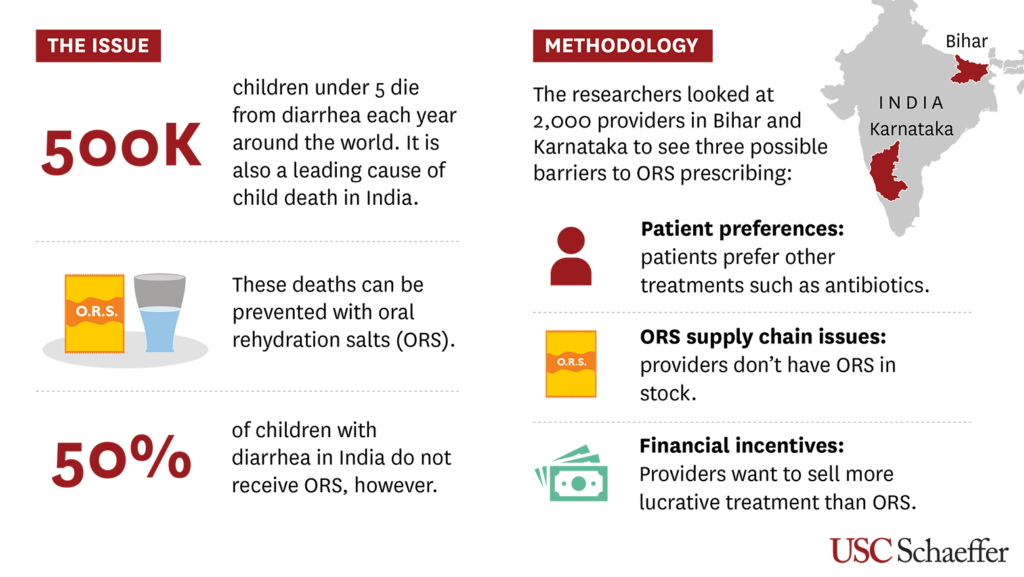

Health care providers in developing countries know that oral rehydration salts (ORS) are a lifesaving and inexpensive treatment for diarrheal disease, a leading cause of death for children worldwide — yet few prescribe it.

A new study published in Science suggests that closing the knowledge gap between what treatments health care providers think patients want and what treatments patients really want could help save half a million lives a year and reduce unnecessary use of antibiotics.

“Even when children seek care from a health care provider for their diarrhea, as most do, they often do not receive ORS, which costs only a few cents and has been recommended by the World Health Organization for decades,” said Neeraj Sood, senior author of the study, senior fellow at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics and a professor at the USC Price School of Public Policy.

“This issue has puzzled experts for decades, and we wanted to get to the bottom of it,” said Sood, who also holds joint appointments at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and the USC Marshall School of Business.

A closer look at childhood illness in India

There are several popular explanations for the underprescription of ORS in India, which accounts for the most cases of child diarrhea of any country in the world:

- Physicians assume their patients do not want oral rehydration salts, which come in a small packet and dissolve in water, because they taste bad or they aren’t “real” medicine like antibiotics.

- The salts are out of stock because they aren’t as profitable as other treatments.

- Physicians make more money prescribing antibiotics, even though they are ineffective against viral diarrhea.

To test these three hypotheses, Sood and his colleagues enrolled over 2,000 health care providers across 253 medium-size towns in the Indian states of Karnataka and Bihar. The researchers selected states with vastly different socioeconomic demographics and varied access to health care to ensure the results were representative of a broad population. Bihar is one of the poorest states in India with below-average ORS use, while Karnataka has above-average per capita income and above-average ORS use.

The researchers then hired staff who were trained to act as patients or caretakers. These “standardized patients” were given scripts to use in unannounced visits to doctors’ offices where they would present a case of viral diarrhea — for which antibiotics are not appropriate — in their 2-year-old child. (For ethical considerations, children did not attend these visits.) The standardized patients made approximately 2,000 visits in total.

Providers were randomly assigned to patient visits where patients expressed a preference for ORS, a preference for antibiotics or no treatment preference. During the visits, patients indicated their preference by showing the health care provider a photo of an ORS packet or antibiotics. The set of patients with no treatment preference simply asked the physician for a recommendation.

To control for profit-motivated prescribing, some of the standardized patients assigned as having no treatment preference informed the provider that they would purchase medicine elsewhere. Additionally, to estimate the effect of stockouts, the researchers randomly assigned all providers in half of the 253 towns to receive a six-week supply of ORS.

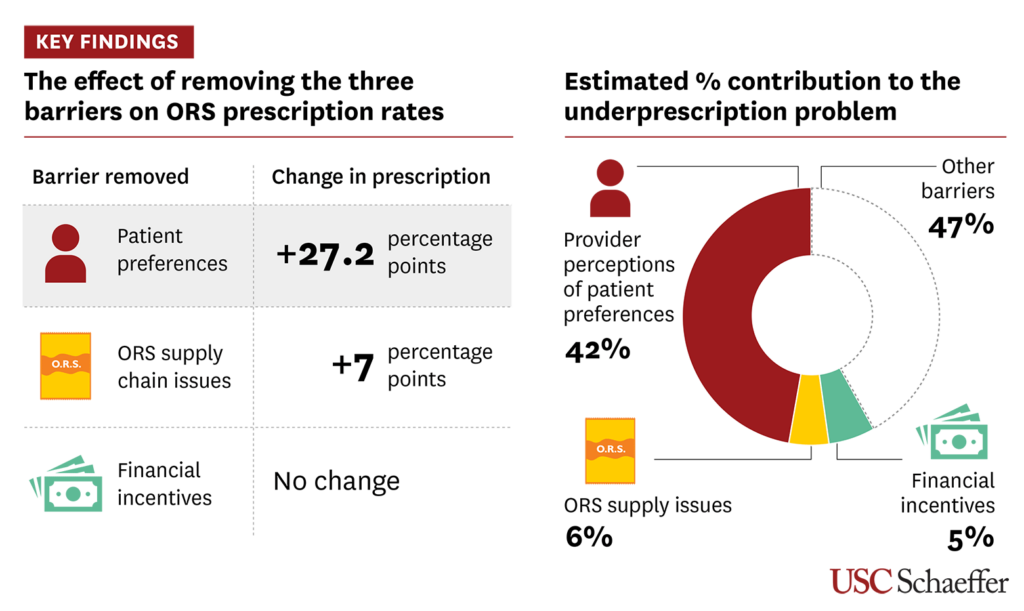

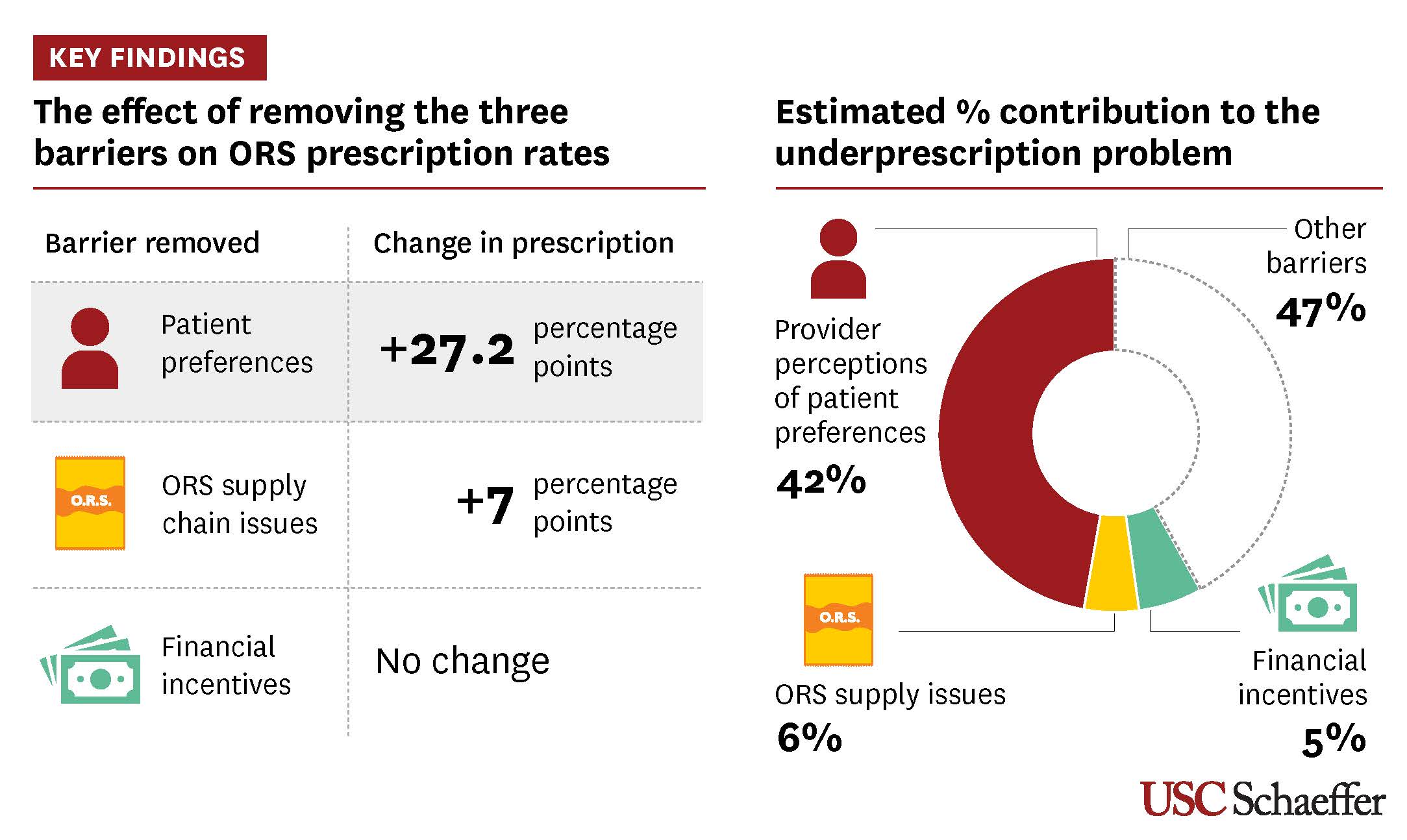

Provider misperceptions matter most when it comes to ORS underprescribing

Researchers found that provider perceptions of patient preferences are the biggest barrier to ORS prescribing — not because caretakers do not want ORS, but rather because providers assume most patients do not want the treatment. Health care providers’ perception that patients do not want ORS accounted for roughly 42% of underprescribing, while stockouts and financial incentives explained only 6% and 5%, respectively.

Patients expressing a preference for ORS increased prescribing of the treatment by 27 percentage points — a more effective intervention than eliminating stockouts (which increased ORS prescribing by 7 percentage points) or removing financial incentives (which only increased ORS prescribing at pharmacies).

“Despite decades of widespread knowledge that ORS is a lifesaving intervention that can save lives of children suffering from diarrhea, the rates of ORS use remain stubbornly low in many countries such as India,” said Manoj Mohanan, co-author of the study and professor of public policy, economics, and global health at the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University. “Changing provider behavior about ORS prescription remains a huge challenge.”

Study authors said these results can be used to design interventions that encourage patients and caretakers to express an ORS preference when seeking care, as well as efforts to raise awareness among providers about patients’ preferences.

“We need to find ways to change providers’ perceptions of patient preferences to increase ORS use and combat antibiotic resistance, which is a huge problem globally,” said Zachary Wagner, the study’s corresponding author, an economist at RAND Corporation and professor of policy analysis at Pardee RAND Graduate School. “How to reduce overprescribing of antibiotics and address antimicrobial resistance is a major global health question, and our study shows that changing provider perceptions of patient preferences is one way to work toward a solution.”

About the study

In addition to Sood, Wagner and Mohanan, co-authors of the study include Rushil Zutshi of RAND Corporation and Pardee RAND Graduate School and Arnab Mukherji of the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore.

This research was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Grant 5R01DK126049).

A common medication could save half a million children each year. So why is it underprescribed?

Neeraj Sood and associates tested three theories as to why oral rehydration salts aren’t prescribed more often. (Illustration/Rika Kanaoka; Image Source/Shutterstock)

Health

A common medication could save half a million children each year. So why is it underprescribed?

A new study by USC researchers explains why kids aren’t getting a cheap, effective treatment for diarrhea.

Health care providers in developing countries know that oral rehydration salts (ORS) are a lifesaving and inexpensive treatment for diarrheal disease, a leading cause of death for children worldwide — yet few prescribe it.

A new study published in Science suggests that closing the knowledge gap between what treatments health care providers think patients want and what treatments patients really want could help save half a million lives a year and reduce unnecessary use of antibiotics.

“Even when children seek care from a health care provider for their diarrhea, as most do, they often do not receive ORS, which costs only a few cents and has been recommended by the World Health Organization for decades,” said Neeraj Sood, senior author of the study, senior fellow at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics and a professor at the USC Price School of Public Policy.

“This issue has puzzled experts for decades, and we wanted to get to the bottom of it,” said Sood, who also holds joint appointments at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and the USC Marshall School of Business.

A closer look at childhood illness in India

There are several popular explanations for the underprescription of ORS in India, which accounts for the most cases of child diarrhea of any country in the world:

- Physicians assume their patients do not want oral rehydration salts, which come in a small packet and dissolve in water, because they taste bad or they aren’t “real” medicine like antibiotics.

- The salts are out of stock because they aren’t as profitable as other treatments.

- Physicians make more money prescribing antibiotics, even though they are ineffective against viral diarrhea.

To test these three hypotheses, Sood and his colleagues enrolled over 2,000 health care providers across 253 medium-size towns in the Indian states of Karnataka and Bihar. The researchers selected states with vastly different socioeconomic demographics and varied access to health care to ensure the results were representative of a broad population. Bihar is one of the poorest states in India with below-average ORS use, while Karnataka has above-average per capita income and above-average ORS use.

The researchers then hired staff who were trained to act as patients or caretakers. These “standardized patients” were given scripts to use in unannounced visits to doctors’ offices where they would present a case of viral diarrhea — for which antibiotics are not appropriate — in their 2-year-old child. (For ethical considerations, children did not attend these visits.) The standardized patients made approximately 2,000 visits in total.

Providers were randomly assigned to patient visits where patients expressed a preference for ORS, a preference for antibiotics or no treatment preference. During the visits, patients indicated their preference by showing the health care provider a photo of an ORS packet or antibiotics. The set of patients with no treatment preference simply asked the physician for a recommendation.

To control for profit-motivated prescribing, some of the standardized patients assigned as having no treatment preference informed the provider that they would purchase medicine elsewhere. Additionally, to estimate the effect of stockouts, the researchers randomly assigned all providers in half of the 253 towns to receive a six-week supply of ORS.

Provider misperceptions matter most when it comes to ORS underprescribing

Researchers found that provider perceptions of patient preferences are the biggest barrier to ORS prescribing — not because caretakers do not want ORS, but rather because providers assume most patients do not want the treatment. Health care providers’ perception that patients do not want ORS accounted for roughly 42% of underprescribing, while stockouts and financial incentives explained only 6% and 5%, respectively.

Patients expressing a preference for ORS increased prescribing of the treatment by 27 percentage points — a more effective intervention than eliminating stockouts (which increased ORS prescribing by 7 percentage points) or removing financial incentives (which only increased ORS prescribing at pharmacies).

“Despite decades of widespread knowledge that ORS is a lifesaving intervention that can save lives of children suffering from diarrhea, the rates of ORS use remain stubbornly low in many countries such as India,” said Manoj Mohanan, co-author of the study and professor of public policy, economics, and global health at the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University. “Changing provider behavior about ORS prescription remains a huge challenge.”

Study authors said these results can be used to design interventions that encourage patients and caretakers to express an ORS preference when seeking care, as well as efforts to raise awareness among providers about patients’ preferences.

“We need to find ways to change providers’ perceptions of patient preferences to increase ORS use and combat antibiotic resistance, which is a huge problem globally,” said Zachary Wagner, the study’s corresponding author, an economist at Rand Corp. and professor of policy analysis at Pardee Rand Graduate School. “How to reduce overprescribing of antibiotics and address antimicrobial resistance is a major global health question, and our study shows that changing provider perceptions of patient preferences is one way to work toward a solution.”

About the study: In addition to Sood, Wagner and Mohanan, co-authors of the study include Rushil Zutshi of Rand Corp. and Pardee Rand Graduate School and Arnab Mukherji of the Indian Institute of Management Bangalore.

This research was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Grant 5R01DK126049).