A genetically engineered herpes simplex virus, when combined with immunotherapy, reduces or eliminates tumors in one-third of clinical trial patients.

Tag: Health

Mindfulness meditation can sharpen attention in adults of all ages

In a USC study, 30 days of app-guided meditation were linked to improvements in how quickly and accurately participants directed their focus.

USC cancer survivorship programs help patients thrive post-diagnosis

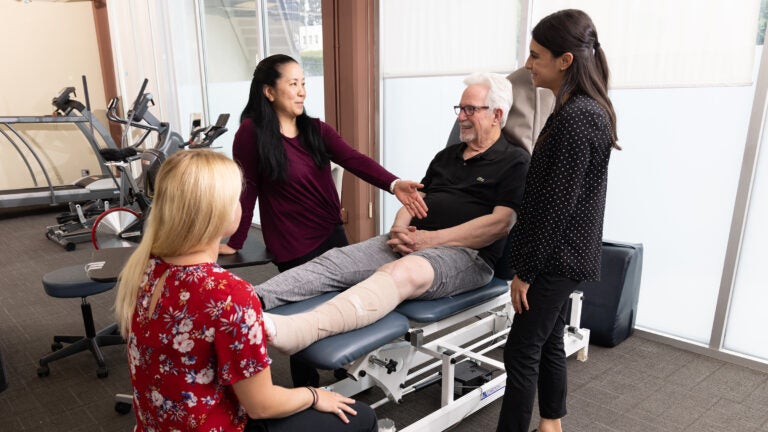

Kristine Kivuls, Kimiko Yamada, Duncan Wigg and Lauren Vera, from left) discuss Wigg’s progress. (Photo/Glenn Marzano)

University

USC cancer survivorship programs help patients thrive post-diagnosis

Cancer treatments are saving and extending more lives than ever. USC practitioners are guiding patients from diagnosis to treatment to facing their post-care future by connecting them with necessary resources.

When Duncan Wigg, a 79-year-old retired psychologist and professor, developed severe pain in his leg and hip in 2022, he had no reason to expect the diagnosis he would receive.

While his private practice orthopedic physicians initially thought he might need a hip replacement, one physician suspected something more serious might be causing the pain. A PET scan revealed a shocking diagnosis: stage 4 lung cancer.

In the medical journey that followed, that orthopedist referred Wigg to Keck Medicine of USC, where a multidisciplinary team of practitioners would bring him back to health — but not without limitations. Struggling with disabling lymphedema (a buildup of fluid that is common after surgery and cancer treatment) and muscle atrophy post-surgery, Wigg credits oncology physical therapist Kimiko Yamada and her team with helping him return to his normal routines and a new level of health.

With cancer patients living longer than ever due to a stream of new therapies and breakthroughs in research, USC practitioners are redefining post-diagnostic care to help survivors thrive in their new normal.

Through an interconnected web of survivorship programs, practitioners from every corner of the university are guiding patients from diagnosis to treatment to facing their post-care future by connecting them to the necessary resources that give them the best chance for successful therapies and recovery. As patients survive longer, and because the cancer journey is so complex, practitioners coordinate across disciplines to ensure that no patient falls through the cracks — or faces the journey alone.

“Her efforts to reduce the swelling and help me regain my strength were very successful,” Wigg said of Yamada. “Keck Medicine’s coordinated and complementary care helped me overcome the effects of the illness and the effects of the surgery.”

An interconnected web of helpers

Yamada’s entry into the field of oncology came early in her career, when one of her colleagues at the USC Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy had a roster of cancer patients that she needed to share. “I ended up working with her patients and fell in love with it,” said Yamada, who is now an associate professor of clinical physical therapy and the director of the division’s oncology physical therapy residency program.

Yamada never gave the roster back and eventually grew her colleague’s practice, becoming a full-time oncology physical therapist and working with a team of surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, and speech and occupational therapists. “I don’t think I’ve found that kind of teamwork at any other practice that I’ve been at,” she said.

USC Physical Therapy has a team of oncology specialists that works with cancer patients and survivors to improve quality of life, reduce pain caused by treatments and meet other unique needs of cancer survivors. Therapies include treatment for fatigue, lymphedema and loss of motion; pre- and post-surgical rehabilitation; exercises to improve activities of daily life; and help reducing stress and improving mood, among others.

The program is just one example of how oncology practitioners from USC’s health science schools and health system are providing services to improve quality of life. Those services include mental health care for patients, survivors and their caregivers, as well as support groups to assist patients and those who care for them as they experience the challenges that a cancer diagnosis presents.

Survivorship begins at diagnosis

The survivorship concept — which considers all living patients who have been diagnosed with cancer as survivors — is an international guideline for all providers who work with cancer patients.

“It was developed to recognize that patients who are diagnosed with cancer at any time have a deep number of traumas that they go through that are not just related to their health, but have to do with the financial aspects, with family, their social interactions and what the future looks like,” said Daphne Stewart, medical oncologist with USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center and clinical professor of medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC. Stewart is also the women’s cancers section chief for medical oncology at Keck School of Medicine’s department of internal medicine.

“There’s a tremendous amount of pressure that gets put on people that we must recognize and address,” Stewart said.

Working within this model, providers like Stewart think about how to work with other providers involved in cancer care, including psychologists, social workers, exercise specialists, and nutrition and weight optimization providers to ensure that patients can take advantage of all the resources the health system offers.

When Stewart arrived at USC in 2023, she developed a clinical breast cancer survivorship program for patients who had finished their primary therapy, including chemotherapy, surgery, reconstruction and radiation therapy. Her team now consists of a medical oncologist, a nurse practitioner who specializes in breast cancer, a social worker and a nurse navigator.

Patients enter the program to improve their long-term mental and physical health and manage financial and social stresses, Stewart said. After speaking with a nurse practitioner, patients are referred to specialists in psychology, psychiatry and physical therapy to engage in therapies designed to help them heal mentally and physically. Survivorship also targets weight loss, blood sugar control and regular surveillance to prevent future cancers. For mental and social support, the program also offers peer groups that meet monthly and give patients a safe space to share experiences.

“It really allows the patients to talk about the overwhelming stress of the big picture of how much this has affected their lives,” Stewart said. Patients discuss cancer-specific changes, such as going through early menopause, chronic pain from treatments, body dysmorphia and other issues.

Stewart remembers a patient who had been lively, social and independent before her breast cancer diagnosis. The experience was traumatic for her, as she received little support from friends and family.

“Being recruited to the survivorship program was a really positive movement forward for her where she could build a bit of a community but also begin to think forward about surviving as opposed to just being focused on all of the side effects and the difficulty of the path that she went through,” Stewart said.

“There are over 18 million cancer survivors in the United States, and over 4 million of these, about 22%, are breast cancer survivors — a number that is expected to rise. We have to acknowledge that this is a large patient population, and as a cancer center, we are thrilled to have a survivorship program so that we can represent our patients fully.”

From survivor to advocate

Mary Aalto, a patient advocate for the USC Norris cancer center, is one of those survivors. A 19-year survivor of stage 3 breast cancer, Aalto returned to the cancer center four years after her successful treatment — at her oncologist’s suggestion — to join the center’s Cancer Survivorship Advisory Council. Soon after, she launched an art series at the center’s cancer resource library featuring the work of survivors with a focus on resilience.

“Survivorship has a lot of recognition now because people are surviving longer,” said Aalto, whose mother died from breast cancer when she was younger. “Twenty, 30, 40 years ago, people weren’t surviving stage 3 cancers, and physicians were just trying to help patients live. Today, survivorship is about quality of life, communication and the doctor-patient relationship.”

Aalto is also the leader of the center’s Patient Perspective Series, a year-round program of events featuring cancer survivors speaking about issues relevant to their peers, including clinical care, physician education, doctor-patient relationships, research, end-of-life laws and resilience. She’s hosted 66 events in her 11 years leading the program.

Aalto says part of the reason she returned as an advocate was the need for patient education and a better understanding of the importance of quality of life as patients, doctors and other medical practitioners craft care plans.

“Despite aggressive treatment, my health is excellent,” she said. “I live in gratitude all the time, and I would not be living in this level of gratitude had I not had cancer. Interestingly, you have to have bad times to appreciate the good times.”

Where courage is born and hope grows strong

Uttam Sinha, director of the Head and Neck Center with Keck Medicine and a professor of otolaryngology — head and neck surgery with Keck School of Medicine, pioneered a survivorship program for his department in the early 2000s.

“Cancer is increasingly becoming a chronic disease; many patients are now surviving longer with cancer in remission,” said Sinha, who echoed Stewart’s belief that society needs to learn how to both take care of and support cancer patients and their loved ones.

He said survivorship programs are essential for providing patients the ongoing care and relevant information throughout their journey — both during and after active treatment.

“There’s so much information in cancer management, but the retention is low because patients are often overwhelmed,” Sinha said. “I usually pair newly diagnosed patients with survivors who’ve been through similar journeys. That peer support is invaluable.”

This mentorship model becomes especially meaningful when patients are facing the physically and emotionally taxing procedures often required in head and neck cancer treatment, such as tracheotomies (to support breathing), mandibulectomies (removal of part or all of the jaw) or glossectomies (removal of part or all of the tongue).

“I understand the process clinically,” Sinha said. “But I haven’t walked in those shoes. A survivor can offer a firsthand perspective — what it feels like, how they coped, how they healed. That’s something only they can truly give.”

The mission statement of the department’s survivorship program, “Where courage is born and hope grows strong,” reflects a core message Sinha and his team promote: encouraging patients to celebrate life, find strength in community and embrace their present, even while acknowledging the losses and uncertainties that accompany survivorship.

The program emphasizes four pillars of well-being: nutrition, stress management, physical activity and sleep.

“The World Health Organization defines health as a complete state of physical, mental, social and spiritual well-being — not merely the absence of disease,” Sinha said. “We tend to focus on physical healing, but the psychosocial aspects are just as important. Our survivorship initiatives aim to nurture those dimensions fully.”

Strengthening patients for the journey

An orthopedic specialist and athletic trainer before becoming a physical therapist, Yamada has now worked in the field of oncology for two decades, helping patients recover better and faster.

“I think everyone has had a loved one, or family member or friend, who has had cancer,” said Yamada, whose grandfathers passed away from cancer while she was in elementary school.

She mentioned that a common misconception is that there is not much to life after cancer and that quality of life is guaranteed to be poor after diagnosis. “I’ll have you know that many of my very first patients from that initial case load are still alive and thriving,” she said.

Optimism in uncertainty

Duncan Wigg’s recovery presents a clear case against that misconception. While he still receives immunotherapy for his initial bout of lung cancer, he describes his health as “excellent.” A little over one year ago, he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. After receiving treatment, he faced another painful recuperation but is expected to make a full recovery. He continues to do intensive physical therapy with Yamada, receives regular preventative care with his team of Keck Medicine specialists and takes trips with his wife, a yoga teacher who, he says, was also essential to his recovery.

“I’m a bit of a miracle,” Wigg said. “But the health care system has come so far in research and knowledge in the last 10 years. I experienced nothing but the best collaboration between oncology, general surgery, radiology and physical therapy — they were all talking to each other.”

Mary Aalto shares Wigg’s positivity. “I am so optimistic about the future for cancer survivors, because it’s getting better and better all the time,” she said. “People are living longer. They’re living healthier. They’re regaining the things in their lives that they loved and that they thought they lost when they were first diagnosed.”

USC cancer survivorship: A multidisciplinary effort

At the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, patient advocate Mary Aalto leads a series of events featuring cancer survivors who are authors, artists, academics and motivational speakers. (USC Photo/Richard Carrasco)

Health

USC cancer survivorship: A multidisciplinary effort

Teams of USC practitioners offer a broad range of support in areas including mental health, nutritional guidance, physical therapy, stress management and chronic pain.

As cancer research and breakthrough treatments help patients live longer, practitioners throughout USC’s health science schools and health system are guiding survivors from diagnosis to treatment to facing their post-care future. Through cancer survivorship programs, multidisciplinary teams of USC practitioners offer a broad range of support in areas beyond surgical and pharmacological intervention to help patients thrive, including mental health, nutritional guidance, physical therapy, stress management, chronic pain and much more. USC units and individuals involved include:

Keck Medicine of USC

USC Head and Neck Center’s patient support group creates a community for patients to share experiences and offer support to each other. The center also has a comprehensive survivorship program, where clinicians from social work to physical therapy to psychiatry work together to provide essential services and support for cancer patients.

The clinical breast cancer survivorship program aims to optimize the long-term mental and physical health of cancer survivors and help them manage financial and social stresses. The program includes interdisciplinary collaboration between clinicians to provide comprehensive oncology support and support groups for survivors and their caregivers.

Keck Medicine’s general Cancer Survivorship Program began in 2014, and provides support to cancer survivors and their loved ones through information and tools to improve and maintain physical health, emotional adjustment and overall well-being. Services include personalized care plans, fertility preservation and restoration, exercise and nutrition support, mental health and wellness support, and other resources.

Keck School of Medicine of USC

Daphne Stewart, clinical professor of medicine at the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Keck School of Medicine and a medical oncologist with Keck Medicine, developed a clinical breast cancer survivorship program in 2023 for patients who had finished their primary therapy, including chemotherapy, surgery and reconstruction. Her team consists of a medical oncologist, a nurse practitioner who specializes in breast cancer, a social worker and a nurse navigator.

USC Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy*

Oncology Physical Therapy: The program empowers survivors of cancer to reclaim their lives through services that address fatigue, loss of motion, pre- and post-surgical rehabilitation, exercises to improve activities of daily life, reducing stress and improving mood, among others.

Golf and Cancer Survivorship: Researchers are studying how physical activities such as golfing can help survivors of prostate cancer maintain a healthy quality of life after treatment.

Post-Prostate Cancer Treatment: Physical therapists work with men experiencing erectile dysfunction and incontinence following a prostatectomy by providing treatment that strengthens the pelvic floor.

USC Mrs. T.H. Chan Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy*

A National Institutes of Health-funded grant is studying whether a customized self-management lifestyle program after colorectal cancer diagnosis empowers survivors to implement and maintain behavioral health and lifestyle recommendations like exercise, diet and alcohol use. The study is still in progress.

In collaboration with Keck Hospital of USC and USC Norris Cancer Hospital, occupational therapists help cancer patients begin the rehabilitation process as soon as possible to reduce hospital length of stay and reduce the risk of hospital-acquired infection. Therapists also help patients develop specialized care plans that involve their social support systems to improve home safety by building functional skills and preparing for the transition back to life outside the hospital.

The department offers the Lifestyle Redesign for Oncology program, which provides a personalized plan to help patients develop healthy routines that include managing pain and energy levels; using adaptive equipment to manage physical limitations; establishing rest and relaxation habits for restorative sleep; learning health nutrition habits and more.

USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology

Gerontology undergraduates have the opportunity to participate in research projects including the Cancer Research Education and Engagement program, designed to increase the translational cancer workforce and reduce cancer health disparities.

USC Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work

USC social workers are crucial members of many cancer survivorship programs across Keck Medicine, the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center and the Keck School of Medicine. These experts help survivors navigate the many resources available through the health science schools and the health system for treatment and recovery, including mental health care for cancer survivors and their caregivers, treatment adherence and decision-making, insurance, housing and transportation.

USC social workers practice and conduct research in cancer-related services and issues including treatment adherence, survivorship, caregiver concerns and cancer-related health care policy.

USC Alfred E. Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences

Medication management: Patients rely on pharmacists to make sure that they’re using their medications to their full potential, answer questions and help prevent and mitigate drug toxicities.

Oncology-trained pharmacists play key roles in clinical trials, from enrollments to monitoring patients to making sure that patients are treated according to trial protocols.

USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center

Patient advocate Mary Aalto leads the Patient Perspective Series, a year-round program of lunchtime events featuring cancer survivors who are authors, artists, academics and motivational speakers.

The multi-ethnic Breast Cancer Survivorship Program offers services to address the needs of breast cancer survivors. The program also provides survivorship education and conducts research and is currently developing a new blood-based test to identify residual disease that may be undetected by mammograms or other forms of imaging.

*Note: The USC Division of Biokinesiology and Physical Therapy and the USC Mrs. T.H. Chan Division of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy are organizationally parts of the Herman Ostrow School of Dentistry of USC.

Common medication for lung cancer symptoms found to limit effectiveness of immunotherapies

High doses of corticosteroids, prescribed to manage cancer-related symptoms or treatment side effects, are the most significant factor in why some immunotherapies don’t work.

Hearing devices improve more than just hearing — they significantly improve wearers’ social lives

A USC study shows hearing aids and cochlear implants make people more sociable and confident, improving overall well-being.

Wildfire smoke exposure, heat stress linked to adverse birth outcomes

Women in climate-vulnerable neighborhoods were especially affected, according to a recent study led by a USC postdoctoral researcher.

Wireless implant is game-changer for personalized chronic pain relief

USC researchers have developed a groundbreaking ultrasound device that could reduce our reliance on addictive painkillers.

Could electric fields supercharge immune attack on the deadliest form of brain cancer?

USC-led research finds that an electric field device placed on the scalp, along with immunotherapy and chemotherapy, may help patients with glioblastoma live longer.

Iron plays major role in Down syndrome-associated Alzheimer’s, USC study finds

Research indicates how iron-related oxidative damage and cell death may hasten the development of Alzheimer’s disease in people with Down syndrome.