Health

Decoding the “C” Word

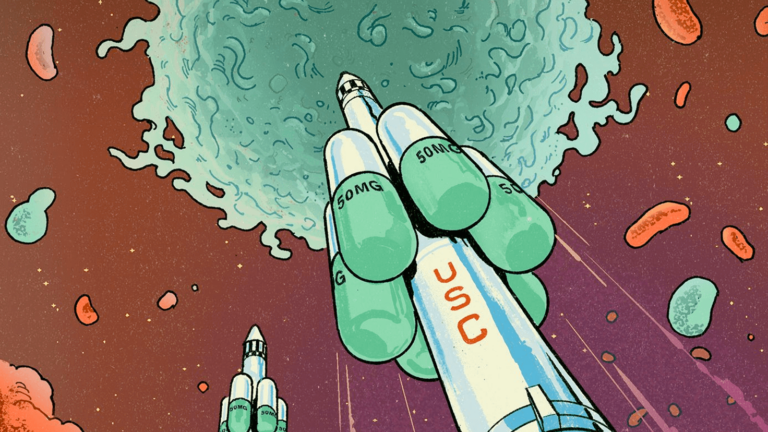

USC researcher John Carpten strives to decode how genes influence cancer — especially for groups hit hardest by the disease

John Carpten remembers the moment he realized his purpose.

In 2010, he was on a call with a team of medical oncology experts, discussing the best course of treatment for a breast cancer patient using the complete genetic sequence taken from her tumor — the first case within a genomic study he led.

Now professor and founding chair of translational genomics at the Keck School of Medicine of USC and founding director of the USC Institute of Translational Genomics, Carpten remembers hanging up the phone and saying, “Now I know why I was born.” After more than two decades of working on human genetics and disease, his research was directly impacting health treatment.

Carpten, the holder of USC’s Royce and Mary Trotter Chair in Cancer Research and USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center’s associate director for basic research, says, “My entire career trajectory led to that one moment. It changed my outlook from having a job to serving a purpose.”

The word “purpose” pops up often when Carpten talks about his work. It’s his mission to untangle the role of biology in cancer to improve treatment — particularly to help close the gaps where Black people and other understudied, underserved populations face a greater burden of disease and worse outcomes from cancer than whites.

Working at the forefront of his field has put him in the position to help set the course for national efforts against cancer.

“This opportunity to advance the understanding, in a way that’s really representative, and then bringing that information to bear in a way that allows everyone to get access to health care innovations — that’s what I fight for,” Carpten says.

‘None of this was planned’

As a child in the Mississippi Delta of the 1970s and ’80s, Carpten earned top grades, stood out on the football field and excelled as a musician into his undergraduate years.

I look at biology as something that’s always changing. The moment you think you have the answers, something changes. I like the continual chase of the answer.

John Carpten

He can’t remember when he fell in love with science, but his family cultivated his passion with encouragement and high expectations. “I look at biology as something that’s always changing,” Carpten says. “The moment you think you have the answers, something changes. I like the continual chase of the answer.”

As a junior biology major at Lane College, a historically Black college in Tennessee, he encountered a magazine that captured his attention, extolling the virtues of genetic engineering.

A college visit to Ohio State University further deepened his interest in molecular biology. “I was fully aware this was an opportunity that not very many young African American men were going to have in 1988,” he says.

‘Jumping into the genetic revolution’

Carpten joined Ohio State as part of a new PhD program in molecular genetics and molecular, cellular and developmental biology, pursuing research into the genes behind muscular dystrophy and spinal muscular atrophy.

“We were just jumping into this genetic revolution, where the genome was going to help us understand more about human diseases, what causes them, how to diagnose them, and how to treat them,” he says.

Then came a postdoctoral position at the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), which was led by Francis Collins. Collins would eventually lead the Human Genome Project — the international research effort to determine the DNA sequence of the entire human genome. Collins and the institute’s scientific director, Jeff Trent, would eventually become Carpten’s frequent research collaborators.

‘My gift was meant to serve a purpose’

In 2000, Carpten earned a tenure-track academic appointment at the NHGRI, undertaking studies into cancer cells’ genes and producing important research on precision oncology.

Applying genomics research such as Carpten’s in the clinic is changing how cancer is treated. Physicians have moved from viewing cancers mainly by their location in the body to approaching them based on their unique molecular makeup. They are also discovering ways to recruit a patient’s own immune system to fight cancers. Narrowly targeted treatments and immunotherapy, which can be more effective with fewer side effects, are increasingly reinforcing — and sometimes replacing — the traditional arsenal of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation.

Carpten’s other budding interest circa 2000 was research meant to quantify — and eventually, reverse — how cancer hits harder in Black people and other people of color. At the time, considerations of diversity, equity and inclusion among study participants weren’t on most medical researchers’ radars. The issue resolved to crystal clarity for Carpten when he found out that only two of the 100 families in a hereditary prostate cancer study were Black — and he knew that prostate cancer disproportionately affects Black men.

It became a call to action. Carpten would help create the African American Hereditary Prostate Cancer (AAHPC) Study Network, a collaboration of predominantly Black researchers and medical doctors working on planning and implementing a national study.

“That was my first foray into cancer health disparities,” he says. “It was the beginning of my understanding that my gifts were meant to serve a purpose. I could help my community.”

‘An opportunity I couldn’t pass up’

Carpten’s concentration on health disparities shapes the diseases he studies, which all disproportionately affect Black people.

Work with the AAHPC Study Network would yield the first genomewide scan for prostate cancer susceptibility genes in African Americans. Later, Carpten conducted the first study to comprehensively compare molecular alterations in tumors between Black and white multiple myeloma patients.

In 2003, Carpten joined the Translational Genomics Research Institute in Arizona. There, he fully recognized the impact his work could have on patients’ lives. His team’s groundbreaking discoveries on genetic mutations enabled researchers to connect study participants with particular mutations to clinical trials of new targeted therapies. Carpten and his colleagues made further strides in precision oncology by finding new molecular targets for potential drugs to treat cholangiocarcinoma, an aggressive cancer of the liver bile ducts.

“Precision oncology studies are particularly impactful,” he says. “They directly affect people’s lives.”

Several factors persuaded Carpten to bring his lab to USC in 2016 — and start a new academic department and research institute in the process. He had an existing precision oncology collaboration benefiting patients at the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center. And he was attracted by the Keck School of Medicine of USC as an environment that encourages work to address health disparities.

But the biggest draw was USC’s unique setting and connection with its community.

The number-one reason was the diversity in California and Los Angeles. I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to apply these medical innovations in a way that patients from all walks of life could access.

John Carpten

“The number-one reason was the diversity in California and Los Angeles,” Carpten says. “I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to apply these medical innovations in a way that patients from all walks of life could access.”

After five-plus years at USC, Carpten continues to drive his mission forward. He leads a cancer disparity research project in collaboration with the University of Florida and Florida A&M University that is backed by a major National Cancer Institute grant. In 2020, he published a paper unveiling a new technique for sequencing the DNA of individual cancer cells within a tumor. And a recently launched effort combining the engagement of Hispanic patients with genomic research in oncology earned a 2021 Cancer Moonshot grant from the NCI.

Carpten attributes much of his success — in his work on health disparities and research contributions — to mentors, collaborators and trainees. In 2021, the American Association for Cancer Research named him a fellow of its AACR Academy. And President Joe Biden appointed him to chair the National Cancer Advisory Board, a development that prompts two words from Carpten: “Responsibility and service.”

“It’s not about me,” he says. “It’s about a national agenda for cancer research and care, the whole continuum. For me, that agenda is reducing the overall mortality rates, and at the same time closing the gaps where there are differences.”

On the biggest of stages, John Carpten remains on mission.

The post Decoding the “C” Word appeared first on USC Today.